Tiger of Sweden Fall 2020 Menswear Collection

/It’s a wonder he waited this long. For fall 2020 Christoffer Lundman turned Tiger’s Eye to that greatest of Swedish icons, Greta Garbo. True to his extremely thorough process, he commissioned a multi-authored book about his inspiration. This season’s took in Garbo’s early life, her Mata Hari–fueled emergence as a global object of focus, and then her fascinating elusive refusal to be subject to it: “I want to be alone.”

Really fascinating were the images of Garbo in 1971 practicing yoga on her balcony or walking to and from her handsome car while in her Klosters exile: These were shot by Ture Sjölander, the Swedish multimedia artist with whom she collaborated to seemingly promote her image as someone who rejected having an image to promote. Reportedly she proposed that Sjolander shoot a series of paparazzi-style pictures because “people seem to like them.” Later the images of Garbo included an altogether less-wanted portfolio: shots of her on the streets of New York City by Ted Leyson, a photographer who stalked the star for a decade. These proved more uncomfortable making, considering they lead to a simultaneous admiration for Garbo’s style and the non-consensual nature of the images’ creation.

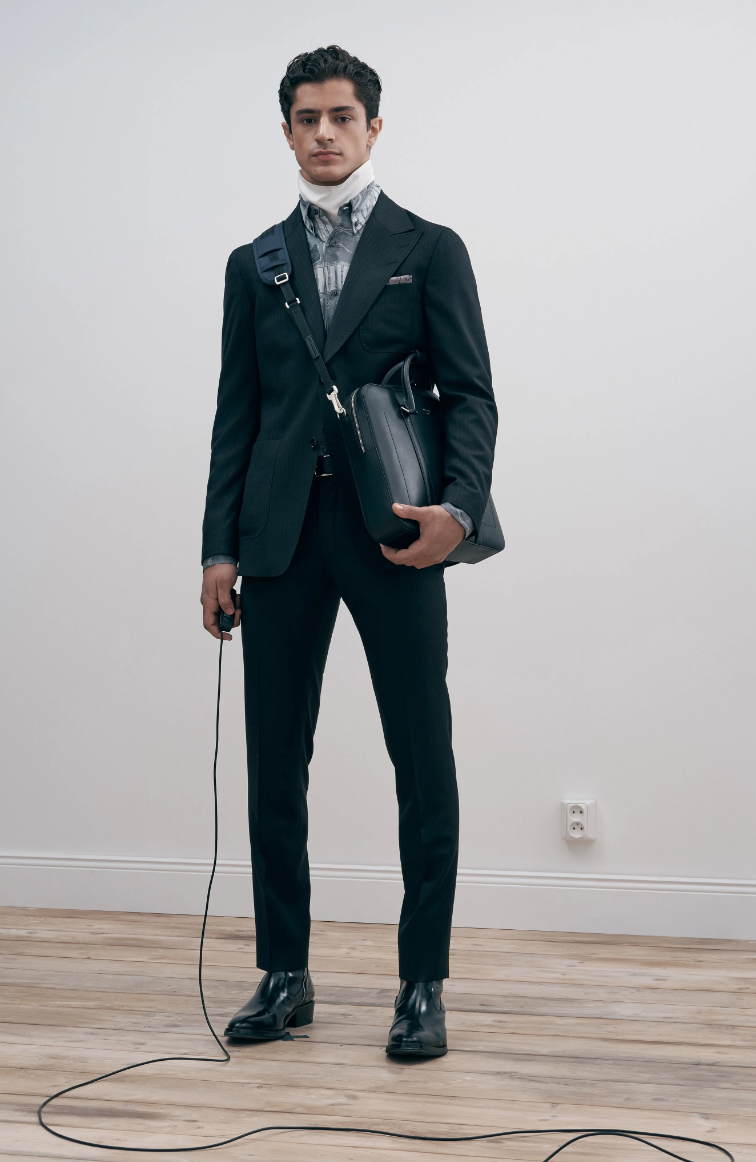

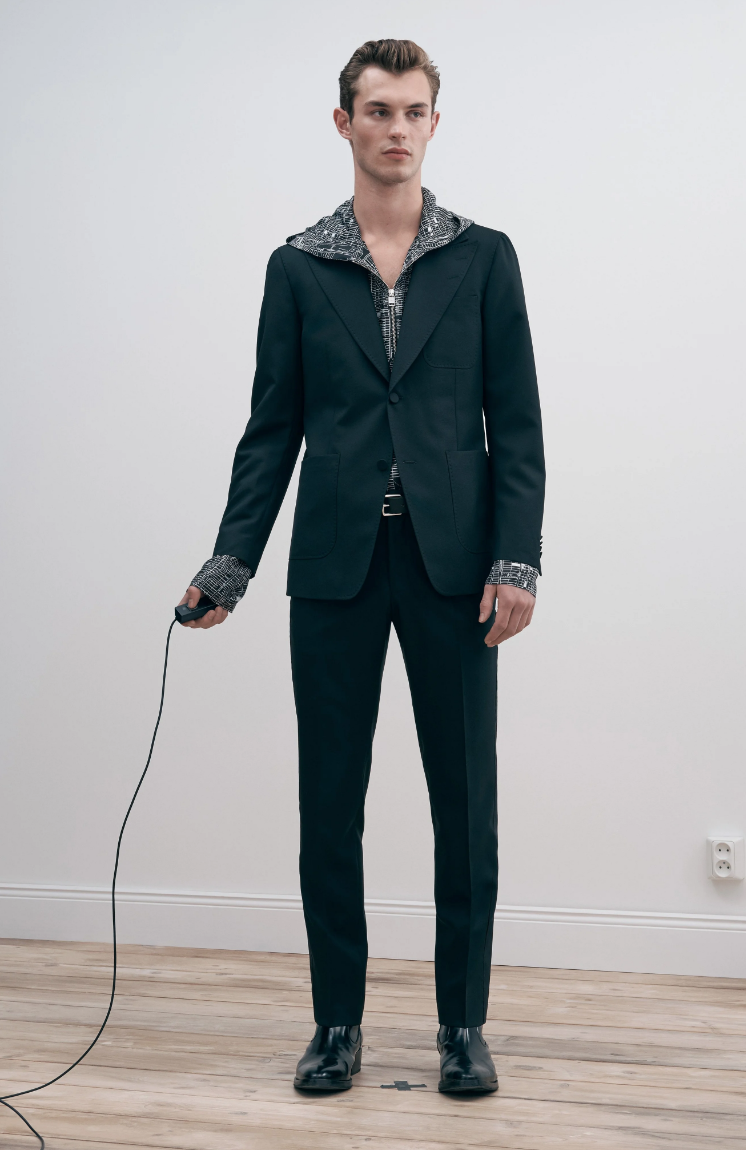

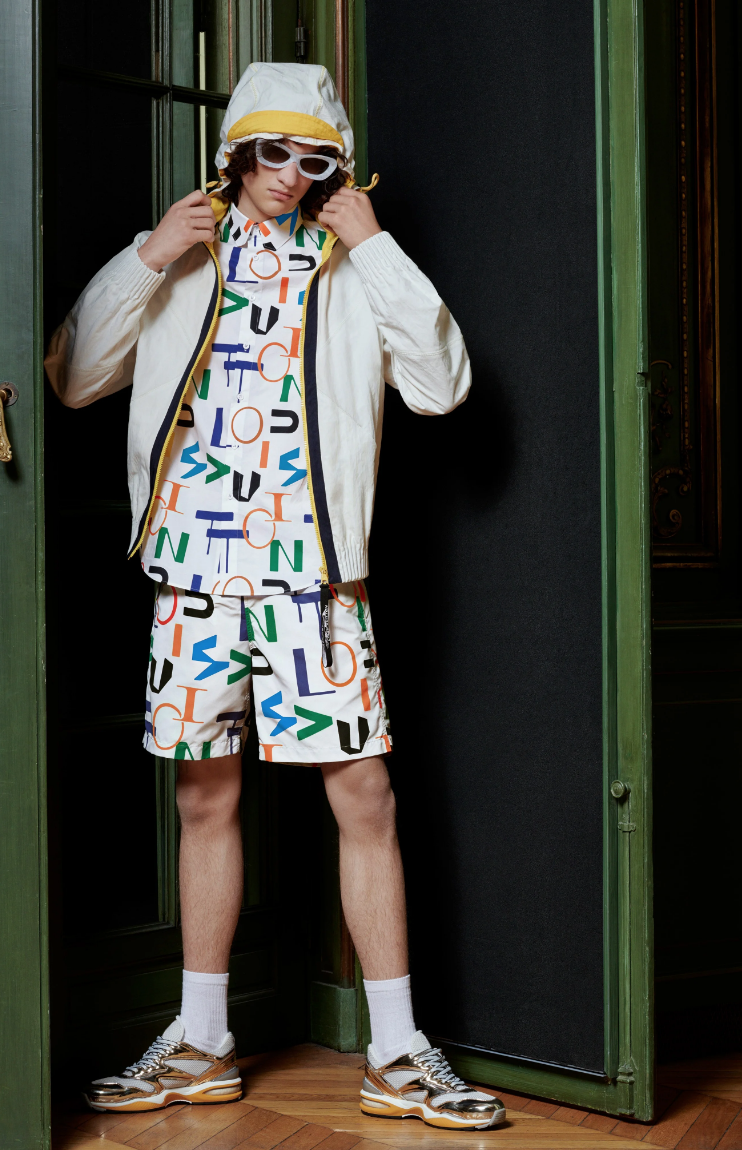

And so the circle wheeled to the collection itself, which was shuttered by its own models as a statement about self image and control of it. The garments serviced self-possession too. From Scandi practical pack-a-macs to foulard shirts printed with Sweden-ized maps of New York City, these were handsome pieces in which to frame yourself. Shirting and jackets featured extra folds of fabric at the neckline to defend unwanted pap shots. The overall atmosphere shared the discreet unassuming masculinity of many of the outfits Garbo was—after her Mata Hari days at least—pictured in.

Source: Vogue

FASHIONADO